Shakespeare in Italy

After Grandad died, I promised myself that I would sift through his papers, pursue any leads, and finish what he had started

When my Grandad died, I was the only plausible heir to his Shakespeare paraphernalia — a dozen books, a miniature bust of Shakespeare, and a folder of papers, in extremely large print, detailing his research into Shakespeare’s supposed visit to Italy.

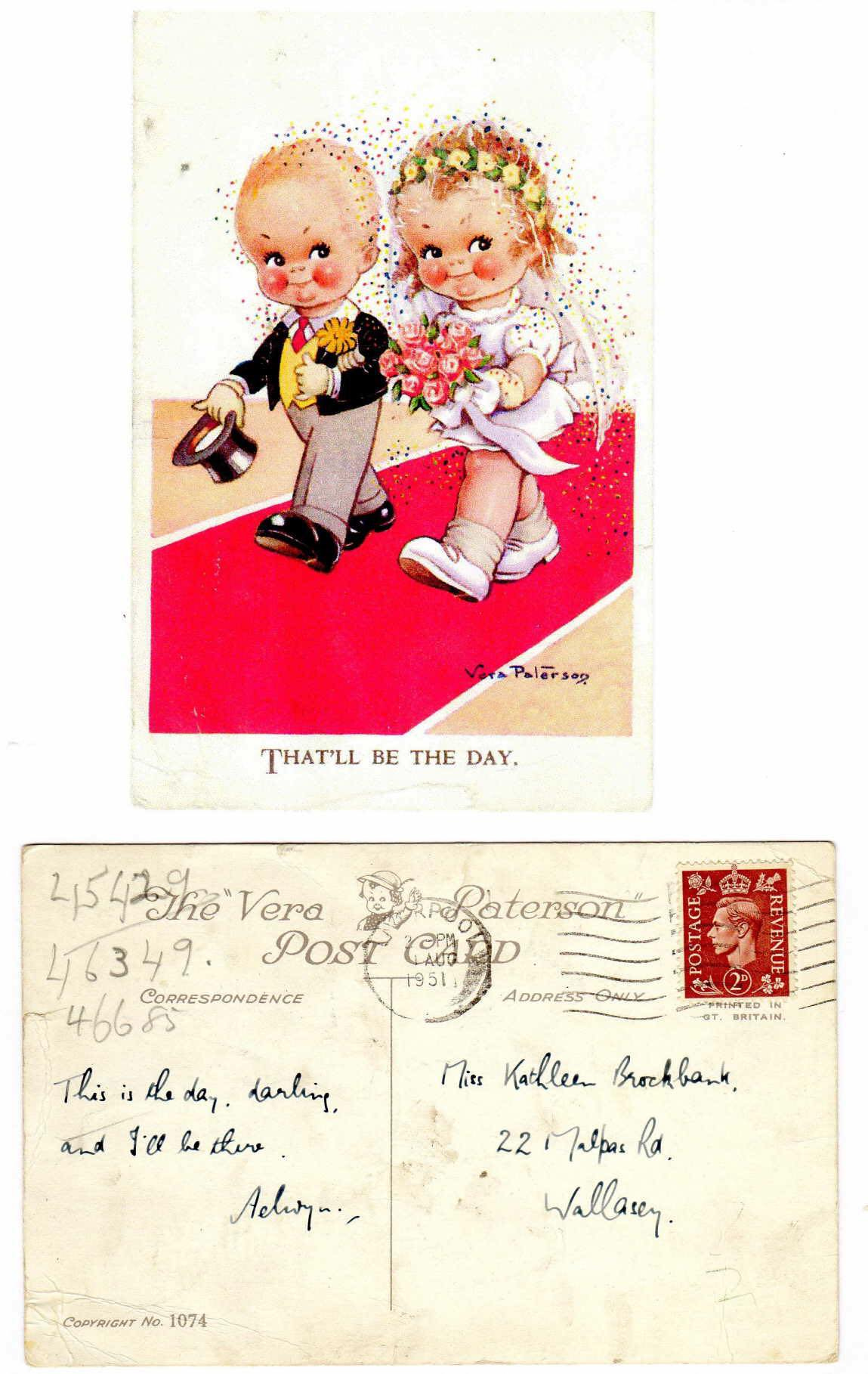

My Grandad, Aelwyn Edwards, studied Geology at Cambridge, and successfully concealed his third-class degree from his two sons for decades. After graduating, he joined the Army to fight in WW2, but was so miserable that he transferred to the RAF, against the wishes of his parents. He was devoted to my Nana, Kath, a somewhat neurotic woman capable of great love. The morning of their wedding, he sent her a postcard to reassure her that he would show up at the altar. She pronounced his name wrong, and so his sons, daughters-in-law, and granddaughters all pronounced his name wrong – until he sheepishly admitted the correct pronounciation, long after Nana’s death and well into his nineties. He loved his grandchildren, country walks, writing, and Wagner.

I’ve had to ruthlessly edit this paragraph – it could have been a lot longer, because Grandad had so many admirable qualities. It is difficult to communicate how loving and how loved he was.

After Grandad died, I took his papers about Shakespeare’s trip to Italy, and promised myself that I would sift through them, pursue any leads, and finish what he had started. He had been so keen to prove this theory, and I wanted nothing more than to vindicate him.

But there were only dead ends.

He had written to the National Archives about an Italian pencil sketch of Shakespeare he’d found. —> They had written back to say that Shakespeare died before modern pencils were invented.

He had identified several geographic facts about Italy which feature in Shakespeare’s plays, which someone could have learned on a visit there. —> As far as I could tell, everything he noticed was also detailed in books that would have been readily available in London at the time.

Short of learning Italian and going to Italy to scour the archives for records of English drapers — in case the theory was true and the evidence existed, and survived, and everybody else had missed it — I felt like I’d done my duty. If there was evidence, Grandad hadn’t found it.

The consensus among historians is that there’s no evidence Shakespeare visited Italy. But from the birth of his daughter Judith in 1585, to the first record of him as a London playwright in 1592, there’s little evidence he did anything. These years are often described as Shakespeare’s “lost years”, because we have no records of his life during this time — but he must have been somewhere.

Shakespeare’s father was a glovemaker and wool trader. This line of work could have easily taken a person, and perhaps his son, to Italy. The absence of evidence doesn’t prove he didn’t go — and we wouldn’t expect to have records of every rural Englishman who made it to Venice.

Grandad had written up one possible narrative which I found compelling — if not evidence — and published it on my uncle’s website in 2007. I’ve reproduced it in full below. I hope you find it interesting.

© The Miracle of the Relic of the True Cross on the Rialto Bridge, 1494 (oil on canvas), Carpaccio, Vittore, Galleria dell' Accademia, Venice, Italy, Bridgeman Images

Shakespeare in Italy

a new theory explaining the Bard's lost years

By Aelwyn Edwards.

There are certain features of Shakespeare's life that have never been satisfactorily explained. For instance, where was he in the years 1585 to 1588, how did he acquire the familiarity with Italian life that is evident in his plays, and who was "Mr.W.H." to whom his sonnets were dedicated? This essay offers a feasible explanation for all these.

x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Young William walked slowly to school that day - his last day at school. His teachers wanted this bright young scholar to stay on in school to the age of seventeen or eighteen, and to go on to university. But his father was adamant that he couldn't afford university, and that he wanted William, his eldest son, to stay at home and help with his business. John Shakespeare ran a glover's business, and also traded in the buying and selling of wool. William had no doubt already accompanied his father on journeys in the course of buying and selling wool, and it was now to be his task to develop this side of the business. It wasn't long before he was travelling on his own, promoting the family business, not only in the immediate vicinity of Stratford, but further afield at the local centre of cloth manufacture at Coventry, and at the great wool marts of Cirencester.

Meanwhile his love life was not being neglected. Anne Hathaway, eight years his senior, became pregnant; they were married, and their daughter Susanna was born a few months later, followed by twins Hamnet and Judith, who were christened on 2nd February 1585, when William was still not yet twenty-one.

William was a bright young man with a good head for business, and in his travels was bound to attract the attention of agents acting for prosperous London wool merchants. It could have been put to him that a lucrative career could open up for him if he were to move to London in the employment of one of these merchants. And so it was that, shortly after the birth of the twins, he moved to London, and so impressed his employer that he was soon offered a post as an overseas agent.

Trade between England and continental Europe at this time was in turmoil, largely due to war in the Spanish Netherlands. Also, the pattern of shipping in the Mediterranean was changing due to the depletion of the Venetian merchant fleet, again due to war, with the result that Venice no longer dominated trade in the area. As a result of these changing circumstances, Queen Elizabeth issued a proclamation on 17th April 1583 authorising fourteen named London merchants to trade with Venice, and at the same time she wrote to the Doge of Venice requesting that these merchants should be granted trading facilities. Two other merchants also traded with Venice at this time, although not strictly authorised to do so. Expeditions were fitted out for the Venetian enterprise, prepared to run the gauntlet of a hostile Spain and North African pirates in order to reap the profits of this trade. William Shakespeare became the agent of one of these merchants, travelling in the interests of his employer's business in Venice, Verona and other cities within the Venetian Empire, and perhaps even trading on his own account. Thus he acquired his knowledge of Italian affairs and customs, and also laid the foundation of his wealth which enabled him, while still relatively young, to become a man of property in Stratford.

These sixteen Merchant Adventurers, and the Livery Companies to which they belonged, were:

Henry Anderson - Grocers

Andrew Banning (or Bayning) - Grocers

Paul Banning (or Bayning) - Grocers

Thomas Cordell - Mercers

Richard Dassell - Mercers

Thomas Dawkins - Grocers

Henry Farington - Drapers

William Garraway (or Garway) - Drapers

Richard Glascock - Haberdashers

Edward Holmden - Grocers

Edward Lichland (or Leachland) - Haberdashers

Edward Sadleir (or Sadler) - Haberdashers

Robert Sadleir (or Sadler) - Haberdashers

Thomas Trowte (or Trott) - Drapers

William Harrison - Drapers

Henry Parvish - Haberdashers

Attempts have made to trace the living descendants of these merchants, perhaps in the forlorn hope that they may possess a chest full of unread documents, but without any conspicuous success.

The Port Books held in the Public Record Office in London give details of imported cargoes, including ports of origin and the names of the merchants, but searches among these books have revealed nothing helpful. The possibility of similar records existing in Venice has been investigated, but all such records relating to the 16th century have been lost. Noting entries in the Books referring to voyages between London and the Baltic port of Lubeck, it is pleasing to speculate on the possibility of our merchant bard travelling along this route, calling in at Elsinore along the way.

Legal records of 16th and 17th century England have long since been thoroughly ransacked for information relating to Shakespeare, and the results well publicised, so there seems little prospect from this source. Legal records in Venice covering the same period are known to exist, so it is there, or in other Venetian cities, that evidence may yet be found. There is always the hope that he put his name to a contract with a local merchant, or that he sued someone, or someone sued him, or that just once he was charged with being drunk and disorderly.

Shakespeare's sonnets were published in 1609, with the following dedication:

TO THE ONLIE BEGETTER OF THESE INSUING SONNETS MR W H ALL HAPPINESSE AND THAT ETERNITIE PROMISED BY OVR EVER LIVING POET WISHETH THE WELL-WISHING ADVENTVRER IN SETTING FORTH. TT.

There has been much speculation concerning the identity of Mr W H and the wording of this dedication. However, one of the Merchant Adventurers trading with Venice, William Harrison, has these initials, and as a prosperous merchant and ship-owner he could well merit the appellation "Mr", and of course, he was an Adventurer. And to whom should Shakespeare dedicate the sonnets but to the one person, his employer, who was instrumental in opening his eyes to the world?

So far, the views expressed above lack the support of direct evidence; nevertheless, this perspective of Shakespeare's life follows a logical and credible course. Experience of life in the Venice of the 1580's has completed the transformation from the provincial schoolboy to the most mature of men. Perhaps evidence for this view still exists, waiting to be found somewhere in England or in the former Venetian dominions.